While thinking about machine learning and AI algorithms I often find myself wondering about how similar some of their processes are to how we (or at least I), as humans tend to perceive, think about and react to the world around us. When I look at self-driving cars, and how they evolved from following a white line on the floor using some basic sensors to being able to navigate any obstacle course better than the best human driver I am amazed at how many sensors, processes, variables and ways to react the car has to go over and choose the best one each millisecond. Not only that, but it also tries to learn from its experience and anticipate as many steps ahead as it can.

Then I realize that if I were to drive the car on the same obstacle course, I would, although mostly subconsciously, go through a similar sequence of processes to handle the task, and just like an autonomous car, I would also try to learn and predict the next sequence of events in order to improve my results on the same task in the future.

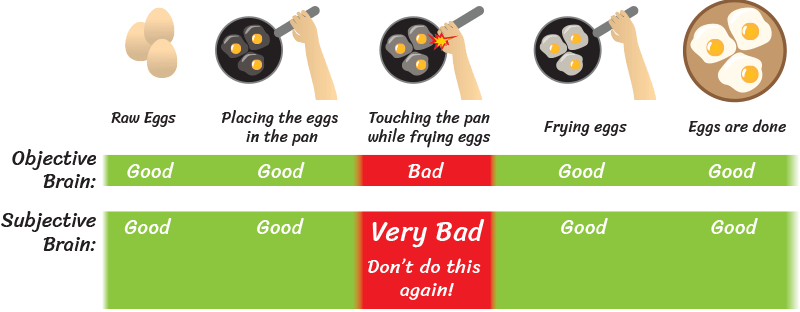

This idea of learning from my experience and, based on that, attempting to predict the future lit up a light in my head. Why do we humans do that? Why do we make AI algorithms do that? The obvious answer is that it’s good to learn from your mistakes: If you burn your hand, you remember the sensation and will be reluctant to try picking up flames again. So at the cost of a minor burn you saved your future self from a greater amount of pain, or even death.

But the thing that made me curious was the other side of the “learning from experience algorithm”; the side that learns from success. When we learn from mistakes, we usually do it the hard and painful way. So we try to get to the root of the problem as much as possible, and differentiate the exact cause of pain and only avoid that specific thing. If you burn yourself on the pan, you don’t give up cooking; you just remember not to touch the pan again while it’s hot. But when you are faced with a pleasurable result you tend to expand that success to include a larger number of events that surround it.

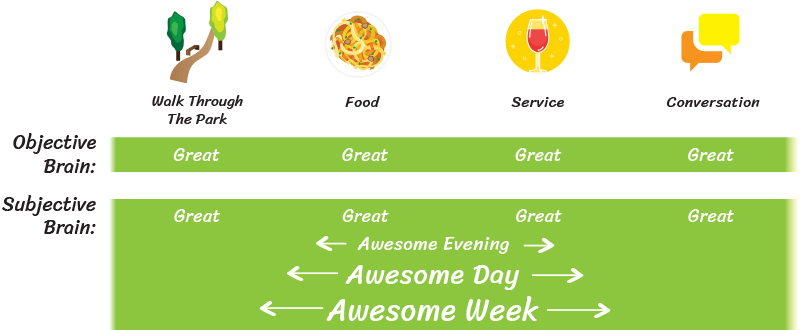

For the sake of proving my point let’s assume you have never went out to eat before and this evening you take your girlfriend out to eat together. Not because it’s a special occasion or you are celebrating anything but only because you didn’t have anything appealing to eat in the house and are going out to satisfy your hunger. And you end up having a superb experience.

The walk through the park to the restaurant was nice, you had a fascinating discussion about something that interests you both, the service was excellent, the food was delicious etc. After this whole experience you will not only remember that the goal of satisfying your hunger is achieved and eating out is an efficient solution. The next time you are hungry and decide to go out you will want to recreate as much of the experience as possible, and rightfully so.

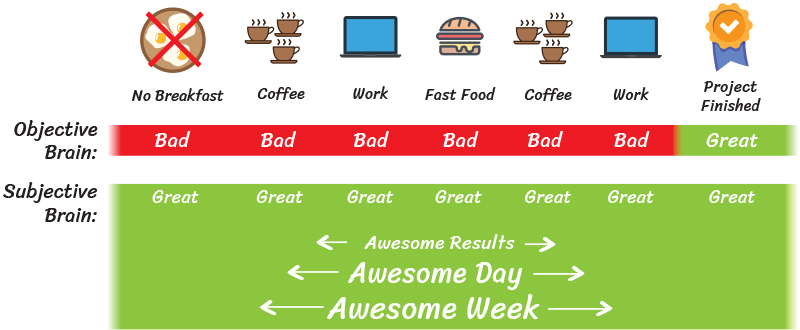

Now let’s take another example. It’s Friday and you have an urgent deadline on Monday and you want to finish your project on time. You decide that you will focus on that 100%, you skip your breakfast, drink 3 cups of coffee, order some food for lunch that you gulp down in 5 minutes, drink another 3 cups of coffee, snack on junk food instead of eating dinner to save time, work until 4am then repeat the same thing the next day. Then, finally, on Sunday night around 2am you finally finished your project, it came out perfect, the next day your client is very satisfied and maybe even gives you a bonus. Well, the result was achieved and you feel great. The fatigue from not sleeping properly, the indigestion from the junk food you gulped just to satisfy your hunger, the stress of meeting the deadline etc., they are all part of the experience now as far as your subconscious is concerned, but being in the past they are significantly overshadowed by the present feeling of achievement.

So why do you tend to remember the achievement part more than the not so great method of reaching it? It’s simple; memory is significantly increased by attention. While you were working on the project you were paying attention to your work and neglecting everything else. So naturally, your memory about things you were deliberately neglecting is going to be minimal.

The next time you will have a project that you have to finish at the end of the month, you will just leave it for the last weekend because “Hey, it’s true that it was a bit tiring last time, but it turned out great in the end!” And after a year of working like that, and you start to really feel burned out, you might also stop working out, start skipping your shower, maybe drink a glass of wine so you can wind down and fall asleep in the evening etc. You might start to realize that this lifestyle is not actually that great, but these bad habits end up being associated with success in some twisted way, to the point that if you finish a project on time, without pressure, without a deadline shadowing you, you might not even feel the same satisfaction. You feel as if you didn’t go through all the usual steps, maybe you feel like you don’t deserve the same satisfaction as if you had put a lot of effort into it and overcame hardship and obstacles to reach your goal.

As you can see, the way we learn from our achievements is a bit different than the way we learn from our mistakes. If you find yourself having some bad habits in your life maybe you should stop trying to find what caused them only in mistakes, unpleasant events, failures or negative emotions. Take a look on the other side and see if your undesired habits are not part of a sequence of events that led you to success and you are just blindly repeating it, good and bad.

If you want to improve your health, you mind and your overall life, try, at least occasionally, to objectively analyze and optimize your activities, even if they are seem to be going great and you are reaching your goals.